Why Text in Vampire Survivors Used to Look Like This

In 2022, Vampire Survivors, a game where you destroy hordes of enemies by just moving around, released. It ended up becoming extremely popular and spawning a whole genre by itself.

At the time, I was working as a software developer for a company who’s product was a complex web application. Therefore, I became a web developer. I wasn’t really interested in game development as the working conditions and pay were known to be less than stellar. However, I quickly realized that the tools used to make web applications could also be used to develop games. Since I could make games with the skills and tooling I was already familiar with, I decided to try it out as a hobby to see if I’d enjoy it.

As time passed, I got interested in the various ways one could use a web developer’s skill set to make games. After some research, I found out that Vampire Survivors was originally made in JavaScript (the programming language that is natively supported in all web browsers) using a game framework called Phaser.

A game framework is essentially a game engine without the UI. While this is not the case for all game frameworks, it sure was for Phaser because it packed a lot of features out of the box. You didn’t have to reinvent the wheel.

I wanted to give Phaser a try after seeing high profile games made with it, like Vampire Survivors and PokéRogue (A Pokémon Roguelike fan game). However, as I started my journey to learn this framework, I quickly gave up because the documentation was confusing. You also needed to write a lot more code to achieve the same results as the alternative I was already using called KAPLAY. I therefore, stuck with it leaving Phaser behind until some time had passed.

As I got more comfortable in my game dev journey, I now wanted to make a small 2D RPG game with a combat system similar to Undertale. In my game, you would avoid projectiles and attack by stepping on attack zones. The player would be expected to learn to dodge various attack patterns. I also, wanted to publish the game on Steam. Prior to this, all games I made were mostly playable on the web.

— SPONSORED SEGMENT —

Speaking of publishing a game on Steam, since games made in JavaScript run in the browser you might be wondering how it’s possible to release them on Steam?

For this purpose, most JavaScript-based games are packaged as desktop downloadable apps via technologies like Electron or NW.js. The packaging process consists in including a full Chromium browser alongside the game which results in bloated app sizes.

However, technologies like Tauri offer a different approach. Instead of packaging a full browser alongside your app, it uses the Web engine already installed on your computer’s operating system. This results in leaner build sizes.

That said, regardless of the technology used, you’ll have to spend a considerable amount of time setting it up before being able to export your game for Windows, Mac and Linux. In addition, extra work will be required for integrating the Steamworks API which allows implementing, among other things, Steam achievements and cloud saves which are features players have come to expect.

If only there were a tool that made both the packaging process and the Steamworks API integration seamless.

Fortunately, that tool exists, and is today’s sponsor : GemShell.

GemShell allows you to package your JavaScript-based games for Windows, Mac and Linux in what amounts to a single click. It:

Produces tiny executables with near-instant startup, avoiding the Chromium bloat by using the system’s WebView.

Provides full access to Steamworks directly via an intuitive JavaScript API.

Has built-in asset encryption to protect your code.

Offers native capabilities allowing you to access the host’s file system.

For more info, visit 👉 https://gemshell.dev/

To get the tool, visit 👉 https://l0om.itch.io/gemshell

You have a tool/product you want featured in a sponsored segment? Contact me at jslegend@protonmail.com

I got started working on my RPG project and things were progressing pretty smoothly until I ran into performance issues. By this point, I’d been developing the game in secret and wasn’t planning to reveal it yet. But I realized I could gather valuable performance feedback by sharing my progress publicly, so I decided to do just that.

It turned out that, while KAPLAY was easy to learn to make games in, it was unfortunately not performant enough. FPS would tank in the bullet hell sections of my game. After doing all kinds of optimizations, I got the frame rate to be good enough but didn’t feel confident it would remain that way as I continued development.

I initially thought of moving forward regardless but quickly changed my mind thinking of all the potential negative reviews I would get on Steam for poor performance. This led me to halt my game’s development. I needed to learn a more performant game framework or game engine. Unfortunately, this meant I’d have to restart making my game from scratch. At least, I could use the same assets. Among the options I was considering learning were Phaser and the Godot game engine.

Since my game was made in JavaScript, I thought trying to learn Phaser again would save me time because I wouldn’t need to learn a different programming language and development environment. I would potentially also be able to reuse code I had already written for my game. Also, Phaser was the most mature and battle-tested option in the JavaScript game dev space as well as one of the most performant. Although I didn’t like how using Phaser would result in very verbose code, the perceived advantages in my situation, outweighed the cons.

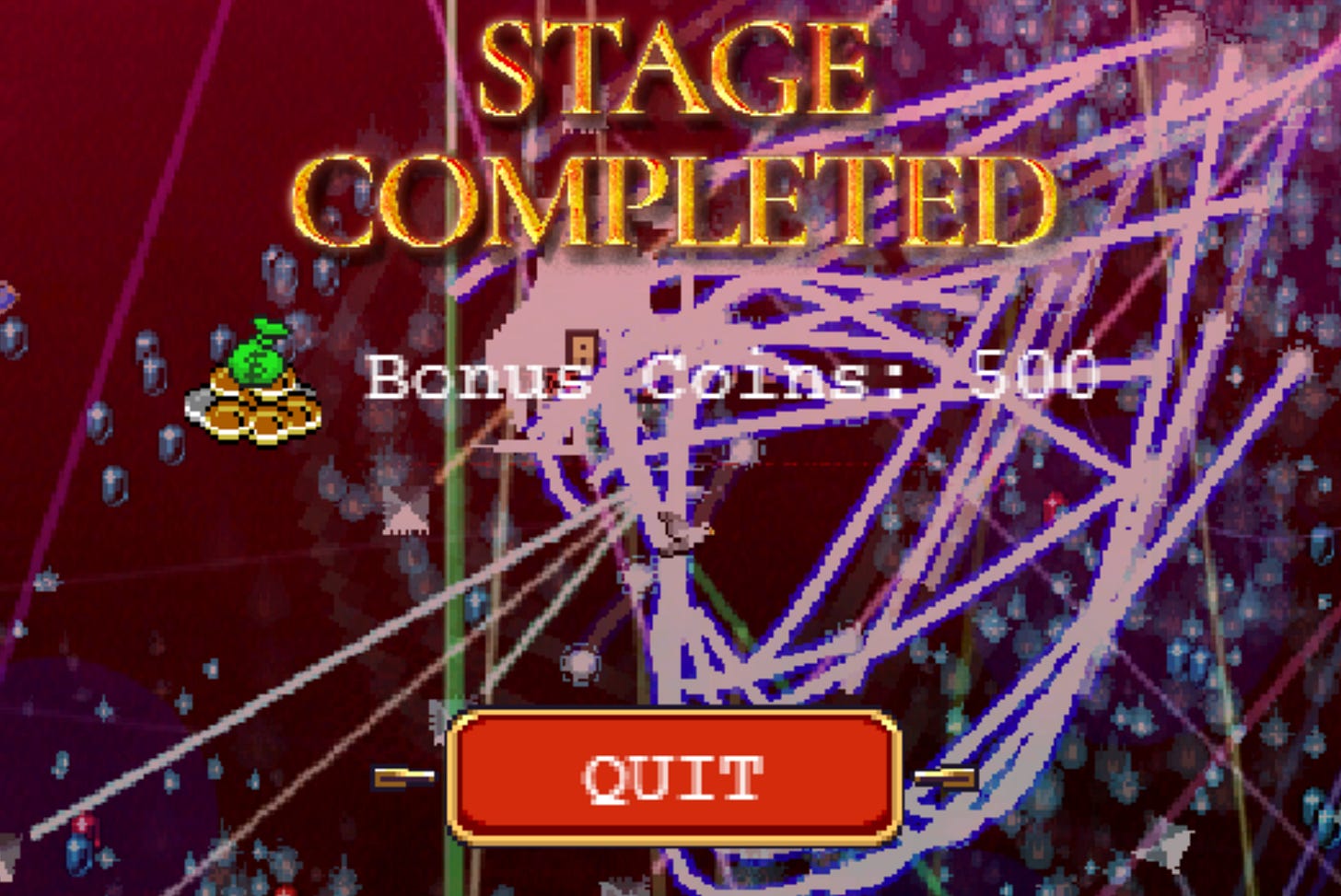

However, one thing that irked me with Phaser, looking at the many games showcased on its official website, was that all of them had blurry text or text with weird artifacts. This was also true for Vampire Survivors and for PokéRogue, if you looked closely enough.

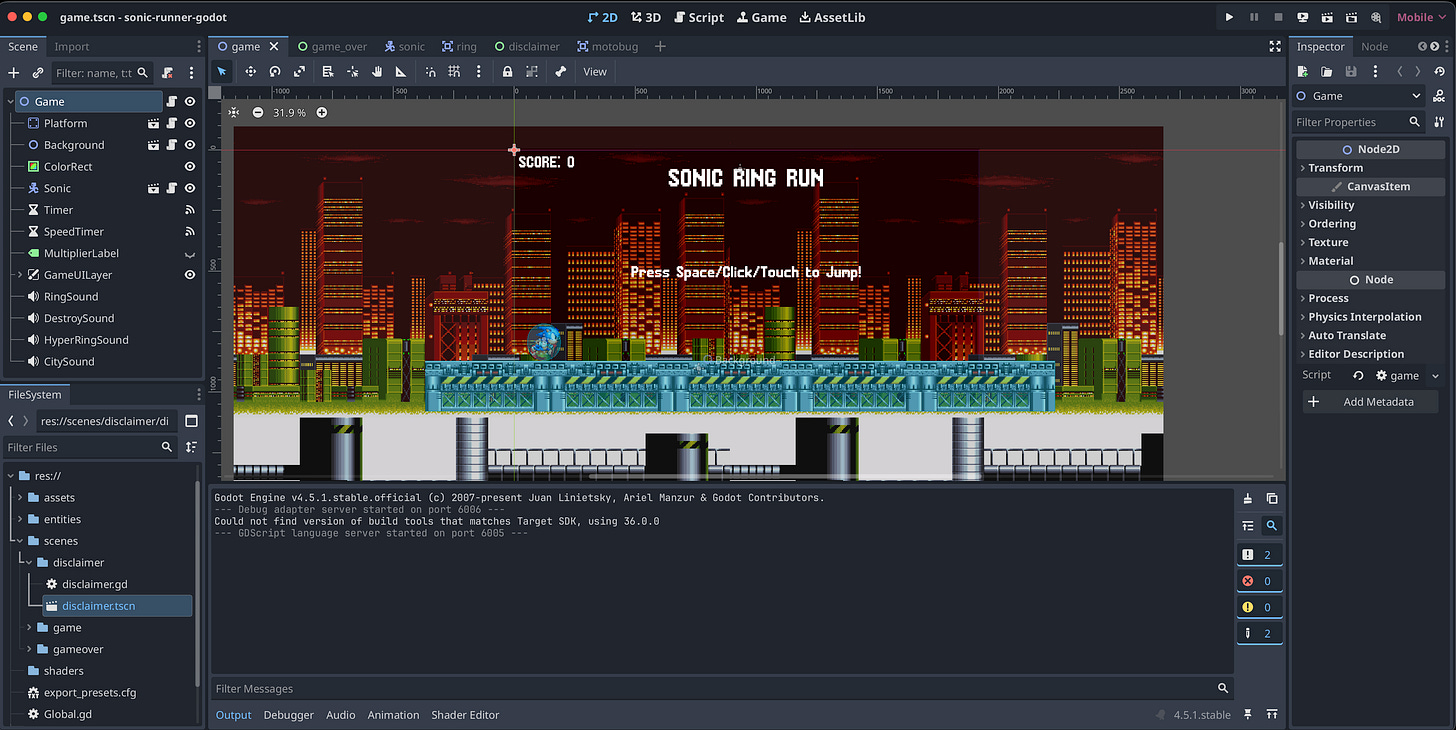

While some may consider this a small detail, it annoyed me to no end. I almost gave up on Phaser again and even started to look for alternatives. Yet, what kept me going was that, in my previous attempt at learning Phaser, I had started working on a remake of my infinite-runner Sonic fan game which was originally made with KAPLAY. I remembered that I had pushed the project on GitHub and left it abandoned. Pulling the project again, I noticed that I had already made significant progress and that the font used didn’t produce any weird artifacts. I thought that I could get around the artifact problem by just carefully selecting which font to use for my games. Because of this, I continued working on the project, learning Phaser quickly in the process.

There’s something to be said about how quickly you can learn a new technology by rebuilding a project you’ve already created. Since you already know exactly what the end result should look like, you can focus on understanding the key concepts of the technology you want to learn. Because each step in rebuilding the project is concrete, you know exactly what to search for. It’s now just a matter of translating between how things are done in the technology you already know VS the one you’re trying to learn.

The rebuild of my Sonic fan game was nearing completion when I needed to display text elsewhere in the game at a different font size. To my dismay, when rendering the font at a smaller size, the artifact problem, which I thought was gone (at least with the font I was using), reared its ugly head again. This was a catastrophe. I was already knee-deep with Phaser and didn’t want to switch again. None of the Phaser games I knew of had clean text, so I assumed it was something inherent to the framework. I couldn’t believe I had forgotten to check how text was rendered at different sizes before committing to Phaser. In hindsight, it was a pretty stupid move, and I felt like I had wasted a lot of time for little benefit.

At this point, the proper thing to do would have been to cut my losses and moved on to something else. However, afflicted by the sunk cost fallacy, I thought that there was no way I would give up now. Not after having spent this much time learning Phaser. I needed to fix this issue, come hell or high water.

After some research, I figured out that the reason my text had artifacts, was because of my use of Phaser’s pixel art option.

import Phaser from “phaser”;

const config = {

width: 1920,

height: 1080,

pixelArt: true, // <---

// rest of options omitted for clarity

};

new Phaser.Game(config);Since I was making a game with pixel art graphics, this option was needed so that my game sprites would scale without becoming blurry. Phaser would achieve this by applying a filtering method called Nearest-Neighbor. The issue, however, was that it wouldn’t only apply this to sprites, it also affected fonts, causing artifacts to appear around the text, since fonts don’t scale the same way.

Since Vampire Survivors also used pixel art graphics, it now made sense why the text used to look so weird. The developer probably just applied the pixel art option and called it a day. By the way, the font used in the game is Phaser’s default font, Courier, which is also a font available on many electronic devices by default. It seems like the dev really didn’t care much about this aspect of the game’s presentation. Now that the game has been moved to Unity, text is rendered properly, though still using Courier, as it has become part of the game’s visual style.

However, disabling the pixel art option wouldn’t solve the issue. Text would still render blurry by default, and the sprites would remain blurry as well.

Fortunately, there was a fix for the font blurriness. The text method allowed setting the resolution of the rendered text. Setting the resolution to 4 made it render clearly. Still, this didn’t help in the end because I still needed the pixel art option for my sprites.

this.add.text(0, 0, “Hello World!”, {

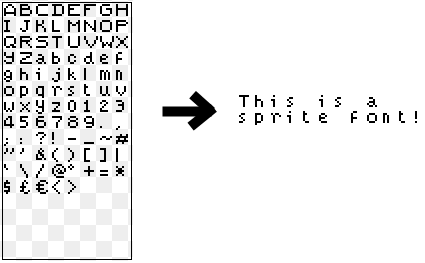

resolution: 4,

fontSize: 32,

});A potential solution to my problem would have been to use a bitmap font, also known as a sprite font. As the name implies, instead of a .ttf font, which most people are accustomed to, a sprite font is stored as an image containing a sprite for each letter. This allows the font to render properly, scaling like other sprites when the pixel art option is enabled.

That said, this solution was a non-starter because each character was a fixed image. I would lose out on the flexibility of a .ttf font that allows for text to be set to italic, bold, etc… I didn’t want to lose on that flexibility and didn’t want the hassle of converting my existing .ttf font.

At this point, I couldn’t believe how much effort was needed just to do a simple thing like render text properly. In frustration, I decided to open the Godot game engine and figure out how to render text just to compare with what I currently had. As expected, I got the font to render nicely automatically. I was tired of having to do this much work for something that I would’ve gotten for free in Godot, this couldn’t go on.

I needed to take a break, so I stepped away from the computer, and the next day, I had an epiphany. Instead of using the pixel art option in Phaser, what if I could apply the Nearest-Neighbor filtering method to each sprite individually? I looked it up, and indeed, it was possible. Using this approach in conjunction with increasing the text resolution to 4 and voilà, I had both non-blurry pixel art and text that rendered clearly without weird artifacts.

this.textures

.get(”sonic”)

.setFilter(Phaser.Textures.FilterMode.NEAREST);

this.textures

.get(”motobug”)

.setFilter(Phaser.Textures.FilterMode.NEAREST);

this.textures

.get(”ring”)

.setFilter(Phaser.Textures.FilterMode.NEAREST);

this.textures

.get(”platforms”)

.setFilter(Phaser.Textures.FilterMode.NEAREST);

this.textures

.get(”chemical-bg”)

.setFilter(Phaser.Textures.FilterMode.NEAREST);

My problem was fixed, but at what cost? I had wasted an enormous amount of time on something that was given for free in a game engine like Godot. I started to consider that going with Phaser was probably a huge blunder.

Seeing how quickly I learned Phaser using this approach of remaking one of my previous projects, it hit me, what if I tried learning Godot the same way?

Without waiting further, I jumped into Godot. As expected, it was very easy to learn considering I knew exactly what to search since my project’s requirements were crystal clear. It was only a matter of looking up how things were done in Godot for each piece of functionality I needed to implement.

GDScript, the programming language used in that engine, was also very easy to pick up and felt like Python which I already had experience in.

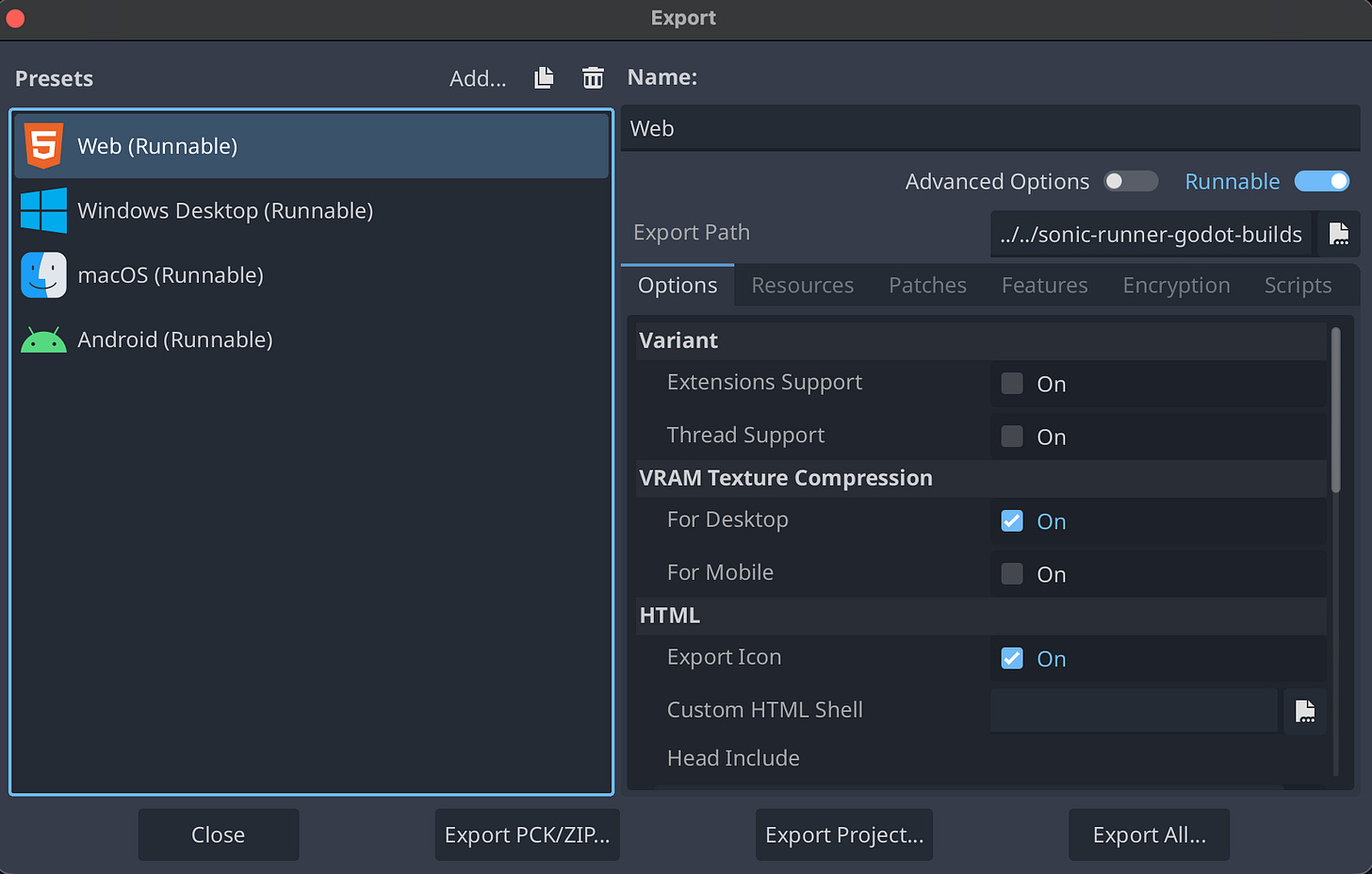

After completing the project, I now had a better view of Godot. Things were intuitive, the code was not verbose and it was an all around nice experience. Before trying the engine, I had the preconception that it no longer supported web export due to the transition from version 3 to 4. I’m happy to report that this is no longer the case. I’ve been using version 4.5, and exporting to the web is just as straightforward as exporting to desktop.

In conclusion, I think Godot is the right choice for my RPG project. I also want to gain mastery of the engine so I can eventually experiment with creating a game that uses 3D models for environments and props, but 2D sprites for characters. Godot makes developing this kind of game far less daunting. This style has been popularized recently by Octopath Traveler using the term HD-2D, although my real inspiration comes from the DS Pokémon era, which used a similar aesthetic without the over-the-top post-processing effects seen in Octopath Traveler.

That said, I’m now presented with two choices:

Make multiple tiny games in Godot to become more proficient before restarting the development of my game.

Jump into development headfirst and learn what I need along the way, just like I did for the Sonic project.

I’m still thinking about it, but I’d appreciate your input.

Anyway, if you want to try both the Phaser and the Godot versions of my Sonic game, they’re both available to play on the web. Here are the links:

Phaser 4 version : https://jslegend.itch.io/sonic-ring-run-phaser-4

Godot 4 version : https://jslegend.itch.io/sonic-ring-run-godot-version

I hope you enjoyed my little game dev adventure. If you’re curious about the small RPG I’m working on, feel free to read my previous post on the topic.

If you’re interested in game development or want to keep up with updates regarding my small RPG, I recommend subscribing to not miss out on future posts and updates.

I think it's easy to get stuck in the mindset of "not knowing enough" to do the thing you actually want to do. There's always more to learn, especially with something as big as godot. You know several programming languages and different game frameworks - it seems like at this point you have a handle on most of the general game development techniques you need to achieve your goal. I think you should work on your game with the understanding that you will know more as you progress.

Games are such huge projects I think no matter how crystal clear your vision is of it is at the beginning there is guaranteed to be a large amount of iteration as you develop it. Know that there will be mistakes and failures and get to the more important job of iterating on your game design as fast as you can. Godot is very well suited to this task. You're definitely ready.

Been using Kaplay for my own project and have enjoyed the ease of programming with it (I too did web programming prior to being laid off). I've also already started to think beyond to other games I want to build/prototype in the future though and have wondered if it might already be time to start looking at Godot. It'd be a shame to leave Kaplay behind, but I don't know how well it'll be able to handle my ideas past a certain point.