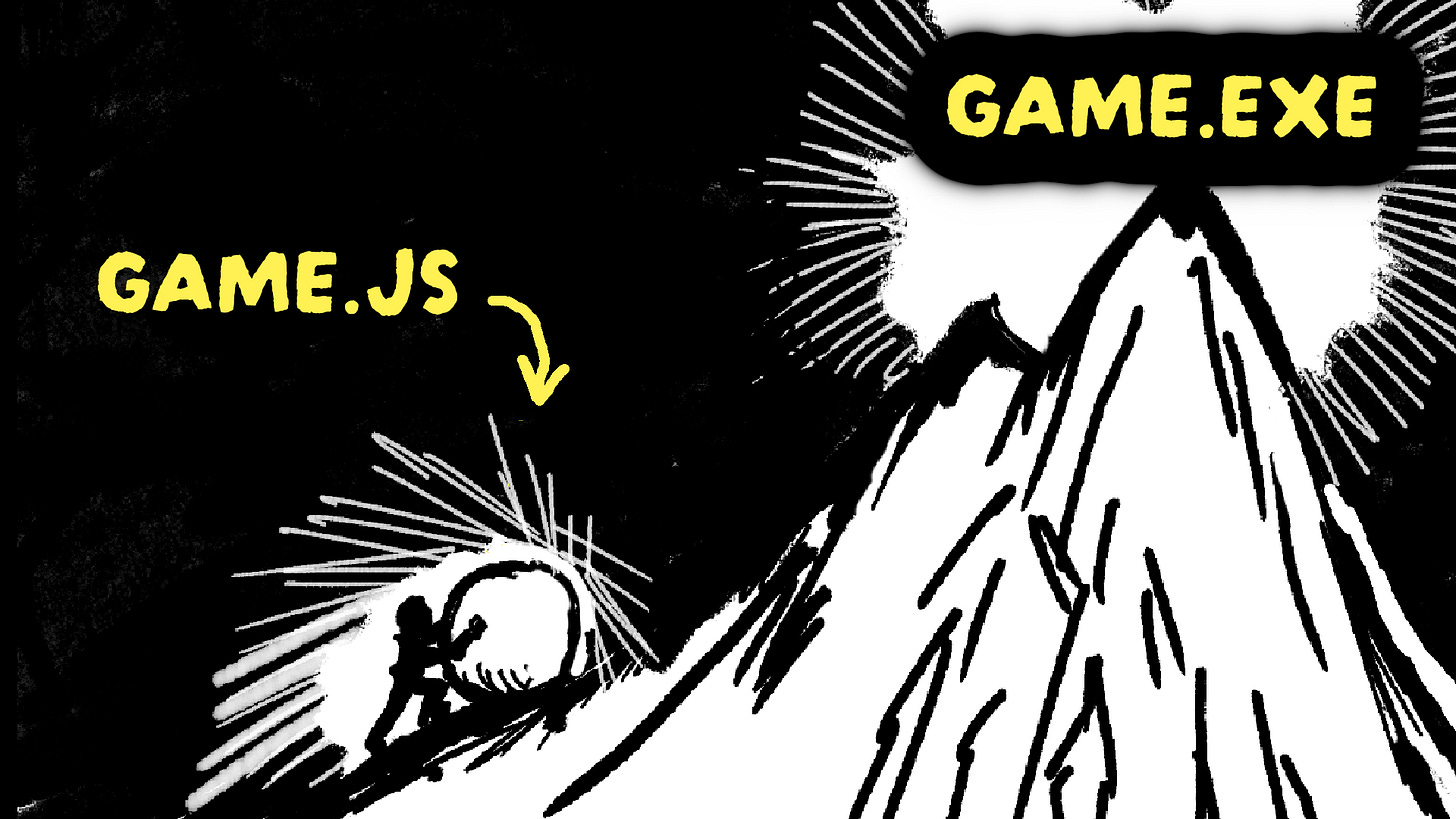

The Struggle of Packaging a JavaScript Game for PC

The story begins after I’d spent some time making web games in JavaScript. At the time, I was looking at the various monetization options that were available.

Unfortunately, I came to realize that the only “realistic” option was to make casual games for web game portals and monetize via ads. Something I did not find enticing. I also wanted to make deeper games which required saving user data. While you can save your player’s data in the user’s browser, this wasn’t reliable as the data could get deleted when the browser cache was cleared. I also didn’t want to pay for servers just to save user data for a single player game.

I also didn’t want to switch to other tools for 2 reasons :

The first, was that I was getting more and more proficient and comfortable with making games in JavaScript using the KAPLAY game library. Every other option I looked into would’ve taken me longer to achieve the same result than in KAPLAY. I also didn’t want to start from scratch learning a new set of tools as it would hinder my game dev progress. I wanted to just build games.

As for the second reason, I felt that making games in JavaScript wasn’t a disadvantage since they would immediately and smoothly run in the browser allowing me to reduce considerably the friction to get new players. My strategy was therefore, making the game available on the web as a demo to gauge interest while putting the full release on Steam.

This is where things got complicated. How would I convert my web game into something that can be installed and played offline on one’s PC?

After doing some research, I came across 5 technologies I could potentially use :

Electron

Tauri

Wails

Neutralino

NW.js

Popular but Bloated

Electron is a technology that allowed developers to build desktop apps using HTML, CSS and JavaScript. Which was perfect since, my games are based on these technologies.

To achieve this, Electron would package your app with a whole Chromium browser. Your app would run in that browser.

That meant every time you installed an app made with Electron, you were also installing a Chromium browser.

Since, Chromium also consumed a lot of memory when running, apps made with it gained a reputation of being bloated. Some users started complaining but still, it did not prevent Electron to gain market share. However, this is irrelevant for games since people are more forgiving when it comes to resource usage.

Most major apps built today that are cross platform (meaning works on Mac, Windows, and Linux) are likely made with Electron. This is the case for VSCode (arguably the most popular code editor), Discord, Slack and many others.

You might be wondering why it’s this popular? This can be boiled down to three points.

Web developers can use a familiar set of tools to build cross-platform desktop apps rather than having to learning tools specific to each operating system.

You have access to most packages and libraries you can find on NPM which means you can build apps really fast.

The fact that it packages a specific Chromium version with your app implies that you can rest assured that your app will render and behave the same way regardless of the user’s operating system. This means less testing is required and therefore less headache on your part.

Despite all of these conveniences, when trying Electron, I found the dev experience quite annoying.

First of all, the way Electron is designed, makes you separate your app into two portions. You could view this as your “backend” and “frontend”.

The “frontend” portion, runs JavaScript that can run in the browser and interacts with the HTML.

The “backend” portion, runs JavaScript within Node.js and does not have access to the UI.

If you check my previous post : How to Start Making Games in JavaScript with No Experience, I explain in more details how JavaScript runs in two major environments.

I recommend checking it out for more details (Video version is also available here.) but to summarize, JavaScript could only be used in the browser before Node.js was invented.

With the advent of Node.js, you could now use JavaScript for backend applications that could run directly on a computer rather than within a browser.

While Electron’s approach of separating these two environments makes sense for more professional desktop app development, it does make wrapping a web game as a desktop app more tedious.

The reason is that to communicate between your “frontend” JS and your “backend” JS within an Electron app, you would need to use a IPC brigde to share only what is needed between the two.

I mostly wanted to do simple things like write my user’s save data in a file on their computer and read that same file. I found doing this in Electron more complex than what other alternatives would end up offering. I didn’t know this at the time. However, The reason I left Electron was due to the whole packaging and building executables process which I found cumbersome.

I tried using Electron Forge which was supposed to help you set up a full build pipeline. I tried using this tool because it was the one linked in the official Electron tutorial docs. What happened after trying to set it up, is that I could only build the app for the platform I was developing on. Since I was developing on a Mac and I’m making a game, having at least a Windows executable is mandatory. (Most gamers use Windows and even Linux since the advent of the Steam Deck and not Macs. I use a Mac mainly for the development experience which I find nicer than on Windows.)

Now, Electron Forge is supposed to allow you to build for the 3 major operating systems if you’re on a Mac. However, I experienced all kinds of issues for the Windows build as I needed to install WINE (which is a compatibility layer for running Windows software on Unix-like systems).

In the end, I was left with two choices, either continue to try to make it work (maybe I would have succeeded with other tools like Electron Builder) or look for alternatives.

I decided to look for alternatives and only come back if nothing else suited my needs.

Interesting but I Don’t Want to Write Rust

The second option I explored was Tauri. It was gaining popularity online and I found the way it approached desktop app development unique.

Instead of wrapping a browser with your app like Electron did, it would simply use the webview available on the user’s operating system.

At first, this sounded great, you get apps that are less bloated in size and trying it out, I found it easy to read/write files to the filesystem.

This was due to Tauri having a JavaScript API you could use for simple things like that. However, for anything more complex, you would have to write Rust.

Rust is a programming language that’s quite complicated. It’s mainly used for lower level development like operating system kernels.

I didn’t want to learn Rust as I had no use for it. Initially, I thought that just using the JS API would be enough. Unfortunately, I didn’t consider something very important.

This whole exercise I was engaged with consisted in packaging a web game to put it on Steam, therefore integrating with the Steam SDK would have been highly desirable.

With Electron, I could have achieved this using the steamwork.js package but with Tauri I couldn’t use this package since the “backend” portion of the app required me to write Rust for anything more complicated than what the JS API offered.

That was a deal breaker.

The fact that it used the default webview to render the app also meant that it wouldn’t render the same across platforms since every operating system had a webview based on a different engine. For Windows, it’s based on Edge which is now Chromium based. For Mac, it’s based on WebKit which is what is used under the hood for Safari. For Linux, it’s based on WebKitGTK which is probably similar to WebKit, but I’m not sure.

Regardless, the way a Tauri app was rendered would force me to do extensive testing on all three platforms to make sure the game was rendered the same way which would just add to my workload compared to something like Electron.

That was another deal breaker.

The last deal breaker was that, when I last used Tauri, you could only generate the executable for the current platform you were developing on. Therefore, I would have to run a Linux distro to build for Linux, run MacOS to build for Mac and run Windows to build for Windows.

It was time to look for something else.

A Similar Approach to Tauri

While I was looking up other alternatives, I came across Neutralinojs and Wails. While they didn’t end up fitting my needs in much the same way as Tauri, I thought it would be interesting to mention them.

Neutralinojs

Neutralinojs is like Tauri but without Rust. It has a JavaScript API for doing simple things like writing to a file, reading a file, etc… For anything more complex, you could hook up a separate backend in any language you want using web sockets.

Wails

Wails is also like Tauri but with Golang instead of Rust. Due to Go’s portability, it was a breeze to set up and to build executables even though the last time I tried it, I was not able to build for Linux, just Windows and MacOS. Golang is also much more approachable as a language than Rust. It doesn’t have a JS API you can use unfortunately. Integrating your game with the Steam SDK is a big question mark since Golang isn’t very used in game dev. Maybe there is a dedicated Go module for this?

The Solution

After getting a bit frustrated with all the options I tried, I was about to go back to Electron when suddenly, I had an epiphany.

Why not look up what existing JavaScript based games on Steam where using? I proceeded to go on the SteamDB website which compiled Steam related data.

Among the data gathered was a list of engines and tools used by released Steam games.

The most popular JavaScript related tool was NWJS with over 5700 games using it.

For reference:

There are over 55000 games made with Unity.

There are over 16900 games made with Unreal.

There are over 2600 games made with Godot.

The info mentioned above can be found here.

I was initially caught off guard by this data because it seemed to indicate, at first glance, that JavaScript was really popular on Steam. This was unexpected because JavaScript is still viewed as a niche language amongst game developers.

After doing some research, I figured out the reason NW.js was used as much as seen on SteamDB was because RPG Maker and Construct were both popular (the former more than the latter) no-code game engines built on web technologies (JavaScript). They would use NW.js to allow their users to export their games as desktop executables.

This implicitly meant that this technology was suitable to use since it was battle tested with so many examples in the wild.

I had initially written off NW.js as a deprecated (even though still maintained) version of Electron since it was created before it and used the same principle of bundling a Chromium instance with your app. However, after having tried it. It’s really simple to use compared to Electron.

First of all, it does not make a separation between the JavaScript that runs in the browser and the one that runs in Node.js. There is no “backend” and “frontend” to worry about and no IPC bridge to set up between the two. Writing logic to save data to some file and reading that file back is really simple.

Secondly, building executables for all 3 platforms is also very easy. When you go on the official NW.js website, you download the needed pre-built binaries for the platforms you need to build for.

Then, you place it in a folder and create a new folder at the same level as the executable with the name package.nw. Finally, you put your source code in that folder.

When you click on the executable, it runs your app using the source code located in the package.nw folder. That’s it.

Now, you can run a command to merge the folder with the executable so it appears as a single .exe that you click and run. What’s left is just to rename the executable with the name of your game and maybe also change the icon with a third-party tool.

You might be wondering, doesn’t this process make it easy for someone to just pirate your game? The answer is yes but it doesn’t matter.

The Love2D game framework also works similarly. It didn’t prevent Balatro, a popular game using this framework to make millions even though the source code was easily accessible.

Conclusion

After trying all of the technologies mentioned previously, I came to the conclusion that NW.js is the easiest technology by far for wrapping a JavaScript based game for desktop.

You’re thinking of giving it a try? In that case, I have an exclusive 1-hour tutorial teaching you how to use NW.js to make a space shooter game for Mac, Windows and Linux.

In this tutorial, I’ll teach you :

How to use Vite and NW.js together, so that you can develop for the web (therefore benefiting from hot reloading) while still being able to build an executable that will work as is. We can achieve this by using Vite’s environment variables allowing us to gate code which will run in the desktop version exclusively. This is useful when it comes to writing and reading files from/to the disk which is code that should run only in the desktop version.

How to use NW-Builder to create a script to build executables programmatically rather than having to manually download binaries from the NW.js website.

How to make a space shooter game using KAPLAY.

If you’re interested, check it out here.

If you enjoyed this post and want more like it, I recommend subscribing so you won’t miss out on future publications.

Meanwhile, you can check these out.

How to Start Making Games in JavaScript with No Experience

It’s been a while since I started making web games in JavaScript. In this post, I’d like to share tips that would be helpful for beginners wanting to do the same.

The KAPLAY Game Library in 5 Minutes

Hi, in this post, I’ll try to explain what is KAPLAY and what are its major concepts in 5 minutes. Let’s get started!